When I was first introduced to the European chestnut, I found it as a shrubby and stunted tree barely able to cope with Michigan’s cold winters. It was on top of a dune overlooking Lake Michigan near Grand Traverse Bay. The view was spectacular. It was a cool late October day and the cold wind off the lakeshore left me speechless. The tree’s size was further highlighted by an American chestnut next to it that was in pristine condition growing ever so vigorous and strong. I knew that this particular species of chestnut was probably not adapted to Michigan. I collected two nuts from under its branches thanks to the owner who helped me find them. It wasn’t easy. Deep in the grass, we pryed open a few burrs only to find those two precious nuts.

No matter where I looked, I could not find the European chestnut tree or seeds for my nursery. I need a batch of them for propagation. I knew this tree as the traditional chestnut of European origin used for centuries. I could buy them in the grocery store in a net bag imported from Italy. I knew they were also disease prone and not hardy enough for Michigan. For orchard production, the Chinese chestnut was the best selection and widely adapted to Michigan’s climate and soils. When the seed sources from California opened up a possibility of growing it as seedlings in my nursery, I was all in. I quickly changed my mind when I saw the massive one ounce nuts. My first purchase of 50 lbs of seed led to complete disaster producing only two trees that survived the winters of minus 20F. In my typical nursery fashion, I tried it again. And of course the effect was the same. I still have those two trees in my orchard. There was a tiny gap with sunlight streaming through and I was going to find the source. I saw the light!

Back at my farm, I tried another direction. I used hybrids. These are naturally occurring plant hybrids of mixed parentage created by someone, somewhere spewing out selections overcoming the disease and hardiness issues of yesteryear. As part and parcel of that hybrid population is your European chestnut. Often the American and Chinese are combined in the population of unknown percentages. One such group, was from seed I purchased from nut grower of the late John Gordon. He had the Simpson seed. It was perfection in so many ways. It was from Ohio and considered one of the most prolific. Other seed included the ‘okas’ of which most came from the late Gellatly at his British Columbia farm. I also found another nut grower here in Michigan where I purchased these hybrid nuts in small quantities. I even found what appeared to be the ‘Paragon’ hybrid grown commercially for a brief moment in time. Each time I did this, I was overjoyed at the vigor and health of the European hybrid seedlings. They had beautiful large dark green leaves and a straight growth habit. At the same time, the real world winnowed out the weak plants quickly. The one characteristic that surprised me the most was the immunity to chestnut blight. The callus material when it occurred was substantial. All trees produce callus when injured whether it be a snow storm or blight. Some trees are not able to keep up. Others quickly grow around their wounds. Old trees like humans have difficulty recovering from tramatic events. Blight is one of them.

I was not overly focused on nut production. It was not breeding but finding vigorous trees and creating from seed populations. Blight was a big motivator in these populations. Initially these were tiny groups of trees scattered throughout my farm. There was quite a bit of variation within the European crosses and what appeared to be the pure species types. By growing the progeny from these fast growing seedlings I thought I had tapped into the hybrid popular effect where things ZOOM UP. It was by letting them self seed that further enhanced my forest by creating greater shade and replacement trees if the others succumb to chestnut blight. On most trees, it took a decade to realize this potential. It was the back up plan to the back up plant. Now I had my forest. The European types although small in number were disappearing into the genetically different populations. In the meantime, most of the originals still produce at my farm and contribute to my chestnut forest. I was selecting for one thing only but in reality I was creating the healthiest trees to reproduce themselves loosely based on my subjective experience. In the grafted varietal world, you select one tree out of hundred and then destroy the ninety nine trees. This time the possibilities express themselves on a real stage of ecological theatre where one tree creates ninety-nine trees all of which are kept. It’s reverse orcharding. Selections can be done now or not at all.

Even in the most traditional landscapes, tree crops need greater diversity to thrive. It has to come from outside to get the full effect of a population. The European chestnut in Greece is struggling. A leader in chestnut production, Greece has experienced a huge loss this year due to extreme drought and heat leading to a drop in 15,000 tonnes or 90 % of its average yields. In relation to its cultural importance, the European chestnut in Greece could disappear without the help of humans in some way. Dragging out the irrigation pipes is not much of a solution long term. The people who live in these mountain villages harvest and maintain these trees and forests. Without them the mountains would be deserted. The late Dr. Dennis Fulbright from Michigan State University use to show the nut growers in Michigan some of these wonderful slides on the European chestnut and how it was propagated, used as a tree crop and processed into delicious food. Today the desertification going on in these mountainous regions along with a failing economy tied to the crop and the families that make a living from it are in peril.

This is where creating new seed populations could replenish the lost trees while propelling the tree crop forest forward. You need deep roots. There is a fig tree in a mountainous region of the Sahara Desert that goes down to 450 ft. deep. They found it in a mine shaft deep beneath the sands of the Sahara. It is considered the worlds deepest roots of any tree. It would not surprise me the chestnut is doing that now. It too is a mountainous tree species able to wind its way past the rocks going deep into the subsoil and rocks to catch the rain and snow melt of winter. Grapes do this all the time. My farm is surrounded by grape fields growing out of sand dunes with almost no top soil. Chestnut has the side branching and hair roots that develop along the forest floor. It has several deep structural type tap roots and that go very deep to extract moisture to fill the nuts in the fall. This occurs right at the end of the season where they all fill at once. If there is no rootstock limitations to interfere and slow down the seedling growth you then have a tree able to harness water far greater than before. New hybrid selections as well as existing trees that appear impervious to drought could create the new chestnut forest. This is exactly how Gama grass selections were done. You look for green healthy plants that thrive in the heat and drought in the worst of conditions. Even at my farm with my limited resources and few seedling selections, you can see the chestnut has this power within it. It is obvious in its growth and production of nuts as well as its thick and hairy leaves and stems. If you dig a chestnut seedling up it has a strong deep tap root. If you cut the root, more deep roots follow. How far does that go down? If any indication of the seedling trees I have, the equiavalent of a mature tree would be at least 100 ft. down. This is how hybrid vigor is ZOOMING DOWN into the deep layers of rock and soil underground. A back breeding program is too slow. The best trees already exist. You are solving your own problems while leaving a doorway open for others to follow. This is where the light shines in.

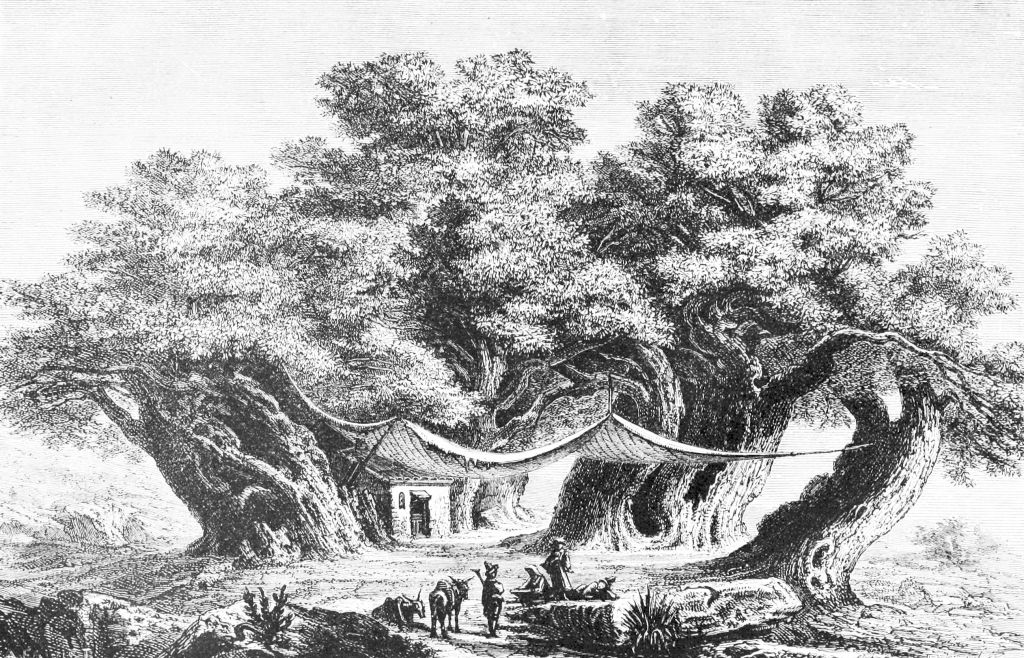

This is the European seedling grown from the nut mentioned in the beginning of my story. Although it rarely produces nuts, the nuts it does produce make very nice seedlings some of which are growing nearby. It has a lot of dead wood in it but the tree has continued its life at my farm finding a portion of the canopy adequate surrounded by hybrid Burenglish oaks and butternuts. The light is bright.

You must be logged in to post a comment.