I saw it first on a walk with my daughter near a sidewalk. As we rounded the corner, a cardboard sign alerted us saying it was “Free’. There it hung on a bamboo stake neatly tied by a small piece of string. Below the sign a cactus sat waiting for a new home. Unearthed in a green plastic pot, the cactus winked at me with its possibilities as I walked by. Afterall, I did have a familiar face. I have grown cactus since I was a child. It was the first plant I had ever grown located directly above my underwear and sock drawer on a dresser top. Today this sidewalk cactus became the cast away plant that a human no longer needed as a flowering perennial in a landscape. It proved too much of a risk. It had big sharp thorns. It had imperceivable small thorns which are almost impossible to remove. The bright yellow waxy flowers were a joy to experience yet there was a cost to this plant as a part of the back yard. It had to go. Maybe it was a new dog or a child. Maybe it was a new stabbing while weeding which then precipitated anger AND remorse. Who knows? Yet, it was also too painful to throw out like other plants. You have some good feelings for the cactus. You are attached to it in some way. I know these feelings of all-things cacti. I too had a lot of cacti at my farm. They ARE cool and so easy to grow. You want the cactus to be adopted by someone that has this openness to it and loves its natural traits. Is love too strong a word? Not for cactus. It’s accommodating and will grow pretty much anywhere. You don’t throw it out. You share it with the world. That is also the way of the cactus. It reinforces the value we hold for conservation and dissemination. Human introductions are the joy of cactus. Let’s move it. Cactus can heal and provide food. Even today it is uncertain where the exact range of certain species of cactus is because it was used so much by people over thousands of years. Never leave home without a cactus pad. It soothes burns, stings and cuts and then can be planted to produce a fruit which also has strong health benefits.

As much as I wanted to, I did not pick up the cactus and take it to my farm. I left it for someone who has not yet experienced its wonder and glory. You see, I am still grieving. I lost my collection. All except one. Here is how that went down in my cactus town.

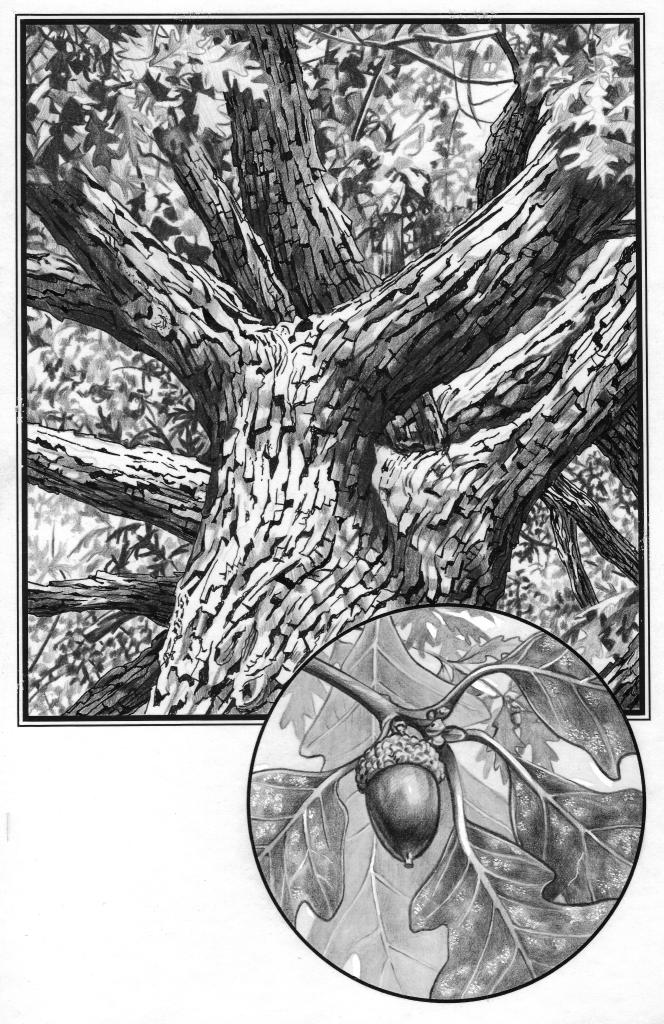

When I first started growing cacti at my farm, I did not have any living germplasm to draw on. I remember seeing a giant field of Prickly pear cactus on a biology field trip when I was a student at Western Michigan University. It was the largest patch of densely packed pads I had ever seen in Michigan then or now. It was easily a solid acre of cacti growing out of pure sand. Since starting my farm, I have been a big fan of seed production of everything. Cactus is easy to grow from cuttings, but I really was on the hunt for seeds. It turned out there are huge growers of cactus in the U.S., and some have the most wonderful seed lists I had ever seen of any genera. I started by purchasing seed from J.L. Hudson Seeds of different mixtures they offered. I grew them on a hill near a boulder I meticulously dug out of the soil in one of my planting beds. The plants began fruiting in three years. Some individuals within that seed mixture were not fully hardy into zone 5. I knew that when I purchased the seed, but it was enough to create my first from seed cactus. It was the edible fruit I was most interested in. I knew that cactus fruit called tuna could be used to make jelly and is said to have great health benefits like aloe vera.

Immediately I gave a pad of one of those seedlings to my mom who planted it next to the back door of her home at the time. There the cactus grew for the next 30 years. My mom took care of my indoor cactus collection when I was going to college for many years. It made her laugh when I handed her the pad. She liked cactus too.

At the rate I was going, Cactus town was in a cycle of slow growth at my farm. It did have a low crime rate. There was no disease. Many species and subspecies of cactus especially the local prickly pear cactus were missing. I began purchasing plants from a few nurseries as well as eBay. eBay came through in many ways because cactus pads are easy to ship, and you find them all over the country including the thornless-glochid free Nopal. Many people like the cactus in their landscape and sell pads off their collections in cultivation. It is easy and safe to do especially if you don’t have soil attached. I tried pretty much everything under the sun. I was trying to build up enough of a collection where I could produce seeds and grow them from seeds in my polyhouses. I began using some of the prairie species from Illinois. Here in Michigan, several selections were given to me from employees who had them in their yard or knew of someone who had wild cactus on their land in some capacity. Finally, between eBay, seeds from collections and wild Michigan cactus, I had enough diversity to produce cactus from seeds. Cactus town was rapidly growing and the rows of them were akin to cactus suburbia. They grew well in southwestern Michigan even with minus 20 F in the winter occurring several times.

To grow cactus from seeds is easy. You whizz the fruit in a blender and then strain out the seeds. The seeds are incredibly hard, and the blades of the blender do not grind up the seeds. We would sometimes run it in reverse to prevent damage on some seeds we did this way. Be prepared for massive amounts of clear gel which is very thick. The whole blender mix would turn to a clear slime with only a handful of fruit. After the seeds are washed thoroughly through a screen, we would put them directly in a flat of a 50-50 mixture of Canadian peat moss and sand. The flats were heavy after they were watered. The seeds were tamped in just under the surface of the soil. It took a couple of winter cycles outdoors in an unheated polyhouse before they sprouted fully. The seeds I was most excited about were species of cactus found in cultivation. I was potentially hoping to find hybrids with good fruit production and with unique low or no thorn selections and large succulent pads for eating. During this time, I found several specialty cactus companies with available seeds with distinct origins like the prairies of Alberta, Canada or the coastline of New Jersey. This combination quickly improved my cactus town in terms of diversity. What I wanted most was full seed production of cactus. This was now possible because the fruiting was complete and some hybrids began to show up in the progeny as well. Now we have cute little baby cactus. When people who propagated for me began planting the cactus flats, they always remarked how cute the little cactus are. They were very cute. Maybe not baby hippopotamus cute, but close in the world of plants.

I was not aware of a looming problem coming. At the time we were just doing polyhouse production of cactus and nothing else. This allowed the dry winter months to put the cactus plants into dormancy very efficiently. A dry winter cactus plant is critical if it’s going to survive long. The pads are shriveled and lose a large portion of their water. As time went on, winters were becoming warmer with much more humidity in the soil and air. There was also less snow and little frost into the ground. This is the perfect conditions for cacti in winter and now it was in short supply. My stock plants outside suffered from a physiological disease called ring spot. Pads were dropping off quickly and soon I lost my ability to produce seeds. Even the plants in the polyhouses were affected because the cold weather was not dry. This was the beginning of the end of my cactus town. One by one through seven different plantings all in different locations died out completely.

There was one bright spot. The cactus pad I gave my mother survived. On one of the last days of closing the family farm, I took a pad near the house and moved it to my farm. Now it was the lone survivor and there it thrived unnoticed by me until I closed my nursery in 2021. Now cactus town had a spokesperson of the glory years and the great times we had together. I named it ‘Elaine’ after my mom. Today it sits under a few holly trees along a road. It beautiful clear yellow flowers take center stage in the summer but few fruit are produced in the fall. The few that are produced are a light green color with no seeds inside. It has no thorns and very few glochids. It looks a bit like a succulent of unknown origin. It has foot long, crispy looking pads that even the deer with take a bite out once in a while. It reminds me of my mom and our beautiful family farm.

Every now and then I get a hankering for increasing my cactus collection again. It’s always the yellow flowers in mid-summer that I see through the grass. I take notice of the colonies along the highway not far from my home. For a while, one prominent thornless planting caught my attention every time I approached the stop sign near it. It was in front of a home and took up a 50 foot long bed. The next year it disappeared when the house was sold. This is the way of human and cactus interaction. Not everyone is a fan. Just last year someone discovered a prickly pear in the upper Peninsula of Michigan. Over the years, a few people have told me about cactus sightings in the upper Peninsula of Michigan. However, no one likes to share their locations because it falls into two equally destructive categories. One is the ‘not very bright idea’ when people want to destroy the colony because it does not belong and is considered not native. Number two is also a ‘not very bright idea’ but it has ‘extremely rare and desirable’ stuck to it. Here you do nothing and leave it alone. Either way it is the end of the colony. I tell them not to tell me. I don’t want to know. It’s a secret. If you really want biological diversity to continue, you must move it. It shouldn’t be held as a secret by those in the exclusive club of botanists with hands-off attitudes. It’s the cactus way to move. It can heal. It can save. It can provide nutrition. The cacti bring life to places where very few things grow. It’s a leader. Cactus lead and people follow their way to cactus town. Eventually we all meet in the middle thorn free and rich in life. That is cactus town and why everyone wants to live there.

Enjoy, Kenneth Asmus

You must be logged in to post a comment.