Every year is a great joy to harvest American persimmons. This year is no exception. I relish the major brush clearing and grass mowing that is needed for me to obtain the fruit in quantity and quality. To harvest the fruit efficiently I have to flat line the vegetation under the trees to chips and clippings so the fruit drops directly on the mulch and not in the middle of an impenetrable hedge filled with thorny wild black raspberries. This process adds valuable fertilizer to the trees. ALL of the brush is valuable including amur honeysuckle and multiflora rose. Some view these plants as the evil enemies of the native world and other exaggerated claims. Since I have been doing this type of hand clearing with lopers, silky saws, weed whackers and lawnmowers for the last 30 years the soil has improved dramatically. Of course the leaves of the persimmons and the deer and other mammals feeding underneath adds to this benefit. And so has the heavy yields of the native American persimmons responded. This is my entry point into the heavenly sugar fruit domain.

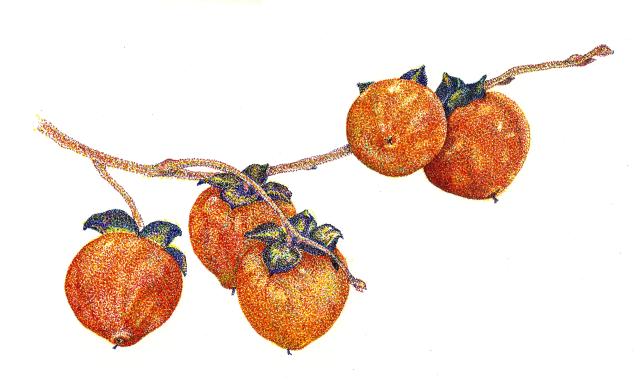

To achieve the best quality fruit requires heat units above 50 F for extended periods of time in the fall. Then the thirty percent sugar range and the smooth texture of a date is possible. It’s the only fruit that I know that has to drop free on it’s own to enjoy. You can shake the branches a little to bring down the fruit. But it is not a fruit to pick. It can’t be yanked. It must be plucked like a guitar string. You cannot pick it in the firm stage and ripen later. It is not a banana or a pear. The American persimmon needs to ripen slowly to imbibe the fall weather and bask in the Indian summer weather. A little frost is said to help but heat is what I need the most. Without that, it is an astringent tannin rich fruit fully capable of creating a metorite type of stone called a bezoar while blocking your intestinal tract in the process. Fully ripened on the tree is the only way to go. On a side note, bezoars from animals are saved and polished and used for pendants.

When people ask me what varieties I have, I proudly exclaim none. All of them are seedling trees. Each tree represents a seed source that I was using when I grew them to sell in my nursery as seedlings from a particular variety. They were selected only because they were the most northern in their range and they ripened early in that location where they were discovered. Many varieties are found in central or southern Indiana or Illinois. Other sources brought die back to the ground in winter. The seed sources were better than most but Michigan is different climate wise. It is much more cloudy and cool here. Lake Michigan has a powerful effect where I live. The poor quality of these grafted varieties in Michigan led me to believe that the tree was fully hardy but the fruit quality was iffy and sometimes not edible. So I used the tree as a person would line their driveway with lavender. I went dense with a spacing of 7-10 feet creating a tree hedge of 1600 foot distance. I had to keep in mind that 50 percent of the dioescious population would be male trees with no fruit. This created a seed bank at my farm based solely on geography. I am 200 plus miles north the American persimmon’s ‘native’ range. I called it the ‘ECOS’ seed source highlighting another step in moving the American persimmon in other ‘non-native’ areas where the tree does not grow. Short season and early ripening is the key to success and that is what I looked for in the progeny over time. My time started in the mid-1980’s and continues to this day where I’m actively naming a few of the seedlings for clonal production so it can leave the hedges and join an orchard system.

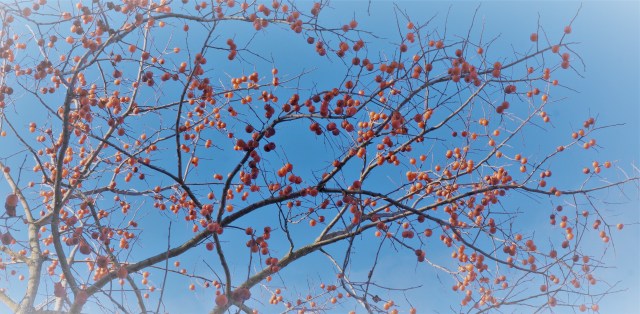

This year I’m really excited about the challenges because of the unfortunate effects of the Canadian wildfires and the cloudy yet rather warm weather. Will it be enough to ripen the fruit is the big question. Patience is needed. The yellow fall color of the leaves reminds me it is persimmon season and I need to move my wildlife cameras to capture the action.

As of the third week in September, fruit is dropping now. When I shut down my power equipment yesterday, I can hear the quiet sounds of a fruit hitting my mulched soils. It is one fruit per thirty minutes. Soon that will ramp up until the rain of fruit becomes deafening and no one can ignore it. I will be there. The deer will come at night. The racoons and possums will dive into the pool and do backstrokes in the fruit on the ground. For a while, a neighbors lost pet pig experienced his ancestral roots here. Even the box turtle hibernated underneath them. Give-give-give is the philosophy of the persimmon. It’s American persimmon season and everyone benefits. Praise the Amur Roses. I’m heading towards the bright orange light of persimmon heaven.

Enjoy. Kenneth Asmus

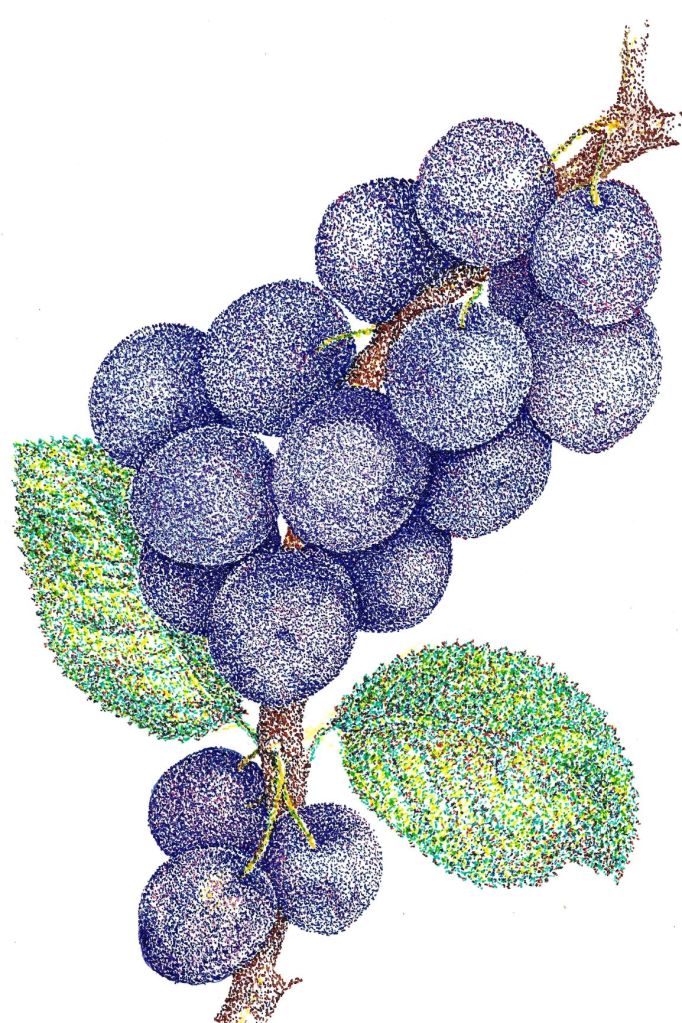

Oikos Tree Crops Artwork by David Adams: Copyright Oikos Tree Crops

You must be logged in to post a comment.